Does UN Peacekeeping work? Here’s what the data says

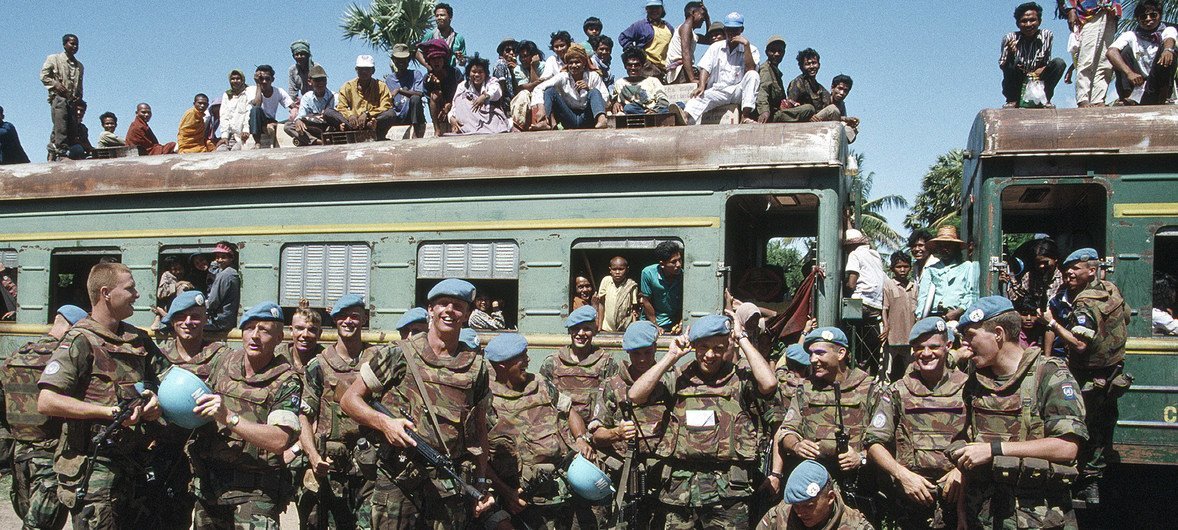

UN Photo/Pernaca Sudhakaran. Dutch troops, from the UN Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC), guarding a train with refugees returning to Cambodia from camps in Thailand (file, 1993)

United Nations, 10 December 2022

Failures on the part of UN Peacekeeping missions have been highly publicised and well documented – and rightly so. But if you look at the overall picture and crunch the data, a different and ultimately positive picture emerges.

The evidence, collected in 16 peer-reviewed studies, shows that peacekeepers – or ‘blue helmets’ as the moniker goes – significantly reduce civilian casualties, shorten conflicts, and help make peace agreements stick.

In fact, the majority of UN Peacekeeping missions succeed in their primary goal, ultimately stabilizing societies and ending war.

“If we look systematically across the record – most of the time peacekeeping works.” That’s the verdict of Professor Lise Howard of Georgetown University, in Washington D.C. Her recent book Power in Peacekeeping is based on extensive field research across different UN peacekeeping missions.

Significant success

“If we look at the completed missions since the end of the Cold War, two thirds of the time, peacekeepers have been successful at implementing their mandates and departing,” Professor Howard says in an interview with UN Video.

“That’s not to say that in all of those cases, everything is perfect in the countries. But it is to say that they’re no longer at war.”

“Peacekeepers reduce the likelihood that civil wars will recur,” she continues. “They also help to achieve peace agreements. Where there’s a promise of peacekeepers, we are more likely to see a peace agreement and peace agreements that stick.”

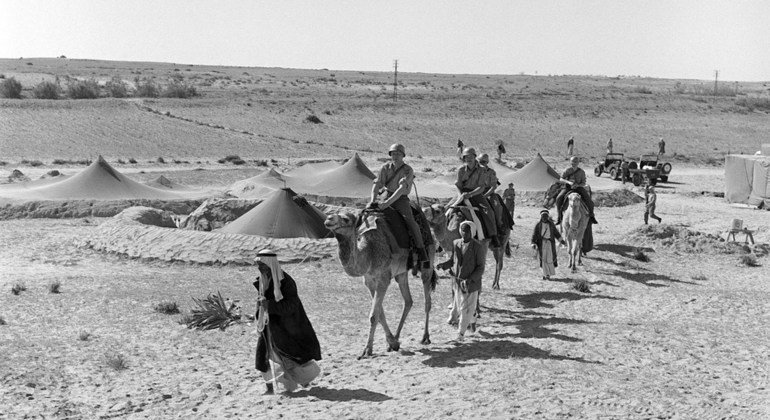

UN Photo/GJ. Swedish peacekeepers from the UN Emergency Force in Egypt (file 1956)

Millions of lives saved

Above all, UN peacekeepers save lives: Professor Howard says that millions of lives have been spared since the creation of peacekeeping in 1948.

The concept of using soldiers, not to fight wars, but to help keep the peace, was born during negotiations in the Middle East in 1948, when the newly-founded state of Israel was in conflict with its neighbours.

One of peacekeeping’s main creators was Dr. Ralph Bunche, an American diplomat who was a senior official with the UN.

“This idea was an innovation in human history – that troops would deploy impartially, so they would not take sides. They would deploy with the consent of the belligerents, so the belligerents would actually ask peacekeepers to help them implement peace agreements.”

For helping negotiate an armistice between Egypt and Israel in 1948, Dr. Bunche was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1950.

UN Photo/M. Grant. A Dutch UN Police monitor with the UN Transition Assistance group in Namibia (file, 1989)

Case study: Namibia

One of Professor Howard’s case studies is Namibia. In 1989, a UN Peacekeeping mission helped end a civil war and supported the first free and fair elections in the country’s history. That was far from an easy task.

“Namibia is a country that has experienced tremendous hardship,” Professor Howard says. “It’s had multiple colonial rulers. It had a genocide. It’s been victim of a regional war, of civil war. But surprisingly Namibia has not fallen victim to this tremendously difficult history.”

Today, Namibia is a stable, upper-middle-income country, with a functioning democratic system – an extraordinary achievement, given that historical background.

The UN mission in Namibia was innovative for its time. 40 per cent of its personnel were women. And Professor Howard argues that UN peacekeeping is most effective, when it is not simply relying on force of arms.

Power of persuasion

“The main form of power they exercised was persuasion. Peacekeepers were there to help reform the political system. Nobody had ever voted in an election before. Peacekeepers were helping to inform citizens of their rights and what it means to elect their own leaders.”

In the complex missions in civil wars, peacekeepers are not only monitoring cease-fire lines, they are also helping to rebuild the basic institutions of the State.

They help demobilize troops. They help reform judicial and economic systems, so that when disputes arise, people don’t have to resort again to violence, to resolve them.

Another key task is protecting civilian lives. During the civil war in South Sudan, UN peacekeepers opened their compounds to hundreds of thousands, providing sanctuary amid intense violence.

Sexual Abuse

There have been times when UN peacekeepers have caused immense harm to civilians – the very opposite of protecting them. A small minority has sexually exploited and abused vulnerable citizens.

The UN has taken measures to prevent peacekeepers from committing acts of sexual violence. Entire battalions have been sent home and there are mechanisms to make sure that victims feel safe to report peacekeeper sexual abuse and exploitation.

The UN has also raised more than $4 million to support victims of sexual abuse and exploitation in the Central African Republic (CAR), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Haiti and Liberia. The Trust Fund helps Member States assist victims and children born of sexual exploitation and abuse.

UNIFIL/Pasqual Gorriz. Ghanaian peacekeepers from the UN Interim Force in Lebanon (file 2020)

Case study: Lebanon

The UN mission in Lebanon is another example of peacekeeping succeeding by using other means than military force. The mission, called UNIFIL, is in a highly volatile area, near the border between Israel and Lebanon. On one side, are the Israeli Defense Forces. On the other, Hezbollah and other armed actors.

One of UNIFIL’s main tasks is to help preserve the peace and diffuse tensions between the Israeli Defense Forces and the Lebanese Army. But, Professor Howard says, the primary form of power that peacekeepers use today, is inducement.

“UN peacekeepers help to keep the peace, not because anyone fears them, but they do see the advantage of having UN peacekeepers inducing people to move toward peace.”

Professor Howard observed peacekeepers in Lebanon first-hand during her field research.

Foot patrols

“In southern Lebanon we often see peacekeepers patrolling on foot. They walk around the local communities. They visit the markets. They talk to people. They’ll talk to the imam. They’ll talk to other local leaders. They’ll set up a medical clinic or provide dentistry services. They also provide a lot of employment in southern Lebanon.”

In other words, UN peacekeepers provide a conduit for talks and for the reduction of tensions. They get to know the local communities and they also provide services. They demonstrate the advantages of peace and stability.

Moving from war to peace

Professor Howard argues that UN peacekeeping is most successful when using persuasion and inducement, rather than direct military force. But whatever the theory behind the success, the data from extensive, systematic studies, shows that the UN’s peacekeeping missions are effective most of the time.

“If we look systematically across the cases, peacekeepers are helping people, in their everyday lives, move from a situation where there’s war and violent conflict to a situation where there is more peace.”

Some of UN Peacekeeping’s successful operations so far:

- Namibia 1989–1990

- Cambodia 1992–1993

- Mozambique 1992–1994

- El Salvador 1991–1995

- Guatemala 1997–1997

- E.Slavonia/Croatia 1996–1998

- Timor Leste 1999–2002

- Sierra Leone 1999–2005

- Burundi 2004–2006

- Timor Leste 2006–2012

- Côte d’Ivoire 2004–2017

- Liberia 2003–2018

The original article appeared here.